Votives, Liquid Libations, & Sacrificial Offerings

Abstract

Conceptualizing object-ness in Ancient Greece requires a contextualized exploration of offering practices, situated within the intricate web of belief systems, social structures, and cultural expectations that defined Ancient Greek society. Sacrificial objects, votive figures, and liquid libations functioned as offerings within a vast network of connection and exchange, fostering relationships between mortals, gods, and the world at large––further reinforcing the significance of object offerings within the collective Greek identity. The primary focus in the gifting of these objects is to please and appease the gods by (a) gifting offerings that are useful to them, (b) sacrificing as a means to favor the eternal nature of the gods, and (c) pouring liquid libations such as wine, milk, or oil as sustenance offerings. The type of gift further corresponded to the level of favor being asked, the status of the person asking, and the significance of the God.

These objects of dedication are immersed within a transitory process, representative of the channel of communication between the offeree and divinity. In this way, these object offerings have agency, not in their ability to move as a function of their free will, but in their interaction with the Gods. These “thank-offering[s]”[1] accompanied rituals and community events, including sacrifices, prayers, and festivals, each being devotional programs serving as moments of connection to the gods. Participating in these spiritual and civic activities was a matter of propriety and duty, essential for maintaining social harmony and avoiding divine wrath. This requital human-thing relationship contained within object offering was an integral aspect of Greekness, with structural forms used to mediate and officiate these modes of contact producing a complex web of interaction. The intimacy of these offerings to the Greeks is a function of their agency, an agency afforded to the objects through Greek ideologies and beliefs surrounding virtue, vows, penance, favor, and gratitude. This is to say that these offerings hold value and importance in the Greek system not just through monetary means, but also through non-secular and relational arrangements rooted in social, cultural, and political paradigms. The treatment of object offerings as dynamic, agential beings, designed to facilitate negotiations between different realms and mediums, move these objects beyond their materiality and into a territory of icons–embodying Greek conceptions of memory, devotion, and desire.

Offerings as Relational, Socially Engaged Beings

These object offerings exist beyond a grid of tangibility, positioning themselves in the larger Greek narrative of object-human fixation, where “objects become values, fetishes, idols, and totems.”[2] In this system, different objects mean differently. Reciprocity is at the forefront of Greek conceptions concerning the connection between the gods and donors; however, every benefit received from this exchange is weighted differently, an idea that Ancient Greeks were conscious of. In the Ancient Greek mind, divine cosmology drives belief, and the gods are thought to be responsible for the health, mortality, and good (or bad) fortune of man. To continue receiving these gifts, Ancient Greeks offered libations, votives, and sacrificial objects in return.[3] The continual gifting of commodities and earthly delights would be reflective of what the individual deemed equitable payment for the fortune and treatment they received from the Gods, a judgement that is a direct reflection of the larger Greek value and belief system dictating what was fair, just, and rightful. So, in thinking about how objects make meaning in a Greek context, the ideational impact of material objects on Ancient Greek systems are a starting point. To consider the “thingness” of these objects, we must go further than discussing the techne of these things, rather we should think about contact, both tangible and intangible.

Animal Votives

Figurine of a Bird and Figurine of an owl are votive offerings that were found in Athens (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Figure 2 is rendered in the form of an owl, a possible reference and connection to the goddess of war and wisdom, Athena. The frontal gaze of the owl draws attention to the eyes, discussed in Homer’s Odyssey as being an identifier for Athena’s perspicaciousnature. This speaks to the modes in which the Athenian people connected visually and spiritually to the gods through allegorical deification and sought to reference sacrality in votive forms, creating a process of meaning-making that functions to convert an object into an active agent.

Figures 1 and 2 are embodiments of a distinct form of object agency, one that animates the spiritual landscape of Ancient Greece and underscores the dynamic interplay between objects, humans, and the divine. The Figurine of a Bird is a terracotta votive offering produced from a mold and likely functioned as an affordable and accessible offering given by a middle-class Greek citizen to a god. The object teeters between ephemerality and permanence, taking the concept of a sacrificial bird and rendering it in an eternal and immortal form–forever holding the attention and favor of the gods, compared to a fleeting animal sacrifice. Further, appropriation of an image of a bird parallels the lived experience of birds as beings capable of traversing territories–reflecting the action of moving from a space occupied by man to a space of the gods. There is also a double interaction produced in the invitation of touch, with the malleability and tangibility of the object relating to the natural condition of a bird through referencing its size, shape, and form, actively aiming to embody the sentiment and spirit of a bird down to its physical composition. This emphasis on touch and physical contact are points of consideration present in the compositional forms of both Figures 1 and 2. These sensory and physical properties facilitate contact, forming a connection that transcends the physical realm and reaches into a spiritual one.

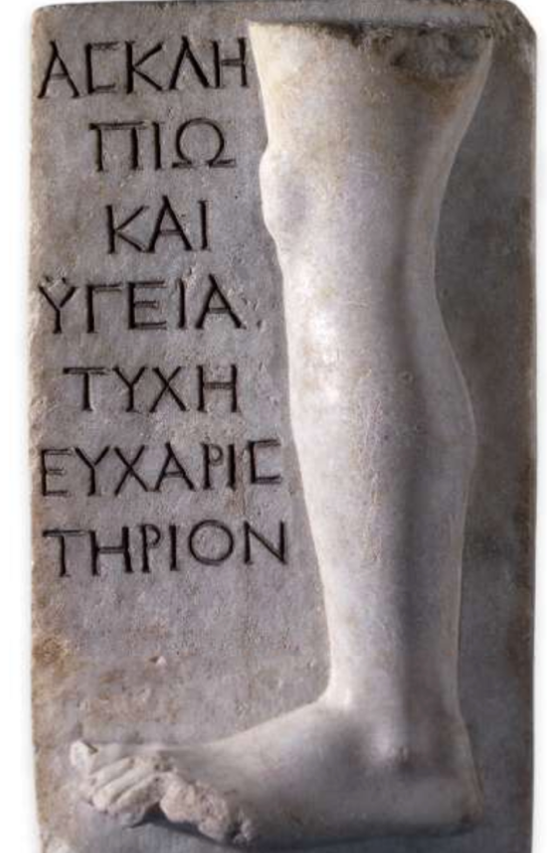

Anatomical Votives

Anatomical votive offerings were often found in burial and ritual deposits, representing a Greek market for figural substitution (Figure 3). These votives were often produced in terracotta and took forms embodying an array of body parts representing physical difficulties and ailments, with parts ranging from arms, legs, and eyes, to breasts, reproductive organs, and genitalia. Once purchased, the body parts were then sacrificed to Asclepius, the god of healing. Some offerings were accompanied by contextual inscriptions detailing the specific recipient of the gift, speaking to the way that these anatomical votives were thought to embody the intentions and prayers of the individual making the offering (Figure 4). Many anatomical votives have suspension holes, allowing the temple priest to hang and display them, pointing to the important role that community played in facilitating offerings. This public display also underscores the complex interplay between private devotion and the communal practice of offering. Anatomical votives are particularly interesting because they have a degree of intimacy and sociality. Further, many of these offerings have unique variations that reference the individual wanting to be embodied in the figural pieces they are gifting to the gods. This communicates the deeply personal nature of a votive offering in the Greek rhetoric–forming a human-thing connection that considers object offerings to be an extension of human autonomy. These object offerings move past their “thingness” because they are anchored and stable in their being, a stability produced and maintained through their entanglements within an assemblage of human-thing relationships and dependencies that make up the larger Greek system of interaction.[4]

Libations

Libations represented a fluid ritual process that involved pouring or drinking from a vessel as a sacrifice to the gods. Libations of wine, oil, honey, and milk were made in celebratory, sacred, and mourning settings; however, the practice can also be observed in the religious and social custom of symposiums. A symposium (pl. symposia, symposiums) was a structured social gathering in Ancient Greece, governed by unwritten rules and etiquette. Much of what we know about symposiums comes from Athens, as it often appeared contextually, and from Plato’s Symposium, which provides the conversation structure of the symposium program. Typically, a select group of individuals would convene by invitation to engage in spirited conversation, debate, and topical discussions, accompanied by liberal wine consumption, musical or lyrical entertainment, and competitive games and contests. Despite the potential for disorder, the ritualistic and ceremonious performance of the symposium was regimented and controlled, with social advances and becoming a part of the most prestigious symposium group being a core objective achieved by performing well in these spaces.

With wine being a central component, the symposiarch–a symposiast designated by the host to lead the symposium program–strategically regulated the wine–to–water mixture. The position of liquid libations is significant not only in symposium behavior and conversation, but also in symposium pottery vessels, as exemplified in a ca. 420 BCE Attic (Athenian) red-figure bell-krater depicting a symposium(Figure 5). The krater, a vessel used for mixing water and wine, illustrates a figural scene of a hetaira playing an aulos, or a flute, entertaining a group of reclining symposiasts engaged in a game of kottabos, each holding a skyphos above their heads and throwing wine grape remains while aiming at a target. This meta-depiction of an image of a symposium on a vessel used during symposiums demonstrates just how encoded the culture of symposia was in Athenian culture––even within the architecture of home.

A kylix, or wine cup, used as a drinking vessel at symposiums performed as an agential being when fulfilling a liquid libation, pointing to the concept of “secular objects [being] adapted and sometimes given special forms for religious purposes.”[5] Kylixes were often not stored in the symposium room proper, but rather set away in a different space separate from the andron. An andron was an image saturated space surrounded by visual and material culture that was reserved for men and also often used as symposium spaces. The Gryphon Mosaic (Figure 6), in the andron of House AVI 3 at Olynthos, is an intimate room designed with intention–to curate a climate of both exclusivity and inclusivity. The construction of the space is also a direct response to the long-standing practice of the symposium. As the symposiast enters the andron, they are stepping over the mosaic, with the mosaic itself acting as the boundary between transitioning zones. As a libation vessel was carried from the room it was stored in, past the mosaic, and into the andron, it underwent an initiation process, moving from a “thing” into an active proxy in the symposium program.

Dionysus, the god of wine, was often honored and celebrated at symposiums, with ceremonious vessels referencing the god and symposiasts offering prayers, singing hymns, and performing honor rituals in his favor. The Vulci black-figure kylixdepicting Dionysus sailing the sea (Figure 7), ca. 540-530 BCE by Exekias, uses heavy visual symbolism driving conversation and comedic ornamentation encouraging interaction from the user, both actively immersing the cup within the symposium program. Overgrown vines and clusters of grapes draped atop the ship’s mast, wine-dark waters concealing the mysteries of the underworld and playing on the idea that water turned to wine, wind blowing into the middle of the sail moving the ship as the symposium moves along. Here, Exekias is offering a prompt to the user of the cup in a symposium setting, one about transforming from one form to another. Much like the seven dolphins painted on the cup, referencing the fate of the Tyrrhenian pirates in the 7th century Homeric hymn to Dionysus, those drinking from the kylix (often referred to as the Dionysus Cup) are magically transformed. This is because, painted on the exterior of the vessel is a large pair of zoomorphic caricature eyes, with the handles acting as ears and the vessel stem a snout, transforming the drinker into a mythic creature appearing as if they are putting on a bestial mask as the vessel covers their face (Figure 8). Designed to be interactive and playful, the “eye cup” effect is only one of the transformations the user undergoes, the other being an alcohol-induced metamorphosis. By using the cup in libations, participants may have sought to establish a connection with Dionysus, invoking his presence and blessings. The Dionysus Cup serves as a tangible link between the Ancient Greek practice of libations and the worship of Dionysus, highlighting the significance of wine and ritual in honoring the god.

Agency of Icons

The allegorical use of personification in the visual art adorning object offerings reflects the virtues of the community, displaying evocations of civil values to the gods and communicating the propriety of the citizens and the prosperity of the polis. This concept can be examined in through worship of Athena, the civic goddess. In visual culture, Athena is often manifested through owls, olive branches, and direct references, including in the red-figure bell-kraterdepicting Apollo and Athena intervening on behalf of Orestes at Delphi (Figure 9), which communicates the values of morality, justice, and wisdom, as personified through the Olympic god. The iconographic depiction of these deified figures on object offerings also personified abstract concepts of virtue, prosperity, and humanity, with “…personification [being] an object of prayer,”[6] valued equally alongside the religious and civic procession of sending off offerings to the gods.

Temples, Sanctuaries, and Treasuries as Intermediaries

The organization of Greek buildings and architecture references the values, beliefs, and practices ingrained within virtually every sector of their social programs. This is especially evident when considering Panhellenic religious spaces, where group identity is forged, maintained, and performed. Treasuries often functioned as sacralized space for these dedications–where the structure itself also functioned as an offering to the gods. The Athenian Treasury in Delphi represents a structural and procedural system of organizing these votive objects, imposing order onto the process of offering (Figure 10). The assigning of a space to the specific purpose of offering communicates to us the Greek conceptions of how, what, where, and how much you dedicate to the gods, giving insight as well to the collective, city-wide scale in which votive offering occurred, enough to justify the erection of a dedicated site. To this point, these defined spaces themselves hold a central position within the larger Greek system, one that values memory and commemoration, and where “the site of dedication is a site marked out as special.”[7] In Figure 10, the treasury space itself is a distyle in antis, featuring Doric columns and a metope depicting Heracles and Theseus, with the support of the pediments coming from the columns and the walls. The Athenian Treasury in Delphi is a structure that deliberately does not want to appear as a temple, unlike the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, rather it references the norms of a temple but creates a clear distinction by functioning as a treasury. However, the treasury was also a space where objects were offered to the gods, thereby “publicly precluded from being commoditized.”[8] This draws on the idea that devotional objects performed as “symbolic inventory,” with entire sacred structures–temples, sanctuaries, treasuries–built around them, framing and granting them with a value beyond their monetary currency and material form.[9] Their role in the larger Greek system is as mediators and facilitators that allow for access and communication to the Gods, centered in “es meson” or in the middle of the two realms, forming a human-thing-god interaction.[10]

The gods were believed to provide moral guidance through the practice of divination, which involved the intermediation and interpretation of oracles, omens, and divine messengers. The priestess and oracle of Delphi, Pythia, was a beacon calling those from cities far and near to visit, offer, and ask questions to Apollo. The Oracle of Delphi was consulted on significant matters, and its prophecies were believed to represent the gods’ will, which helped to prevent any single city-state or individual from manipulating messages from Apollo. Those who violated social norms were thought to be punished by the gods, while those who adhered to these norms were rewarded. This belief system reinforced the importance of propriety, as individuals sought to avoid divine retribution and earn favor with the gods.

The Pan-Hellenic complex at Delphi is an oracle site involved in the cycle of myth making and is valuable in its sacrality and social function. The altars at Delphi are an indicator of sacrifice, marking sacred spaces that form a visual and material record. Delphi as a religious and cultural center assisted the public practice of religion, with structures on the larger sanctuary site proper easily distinguished by three key features:

- An altar

- A defined sacred space

- And/or features that represent a moment of monumentation

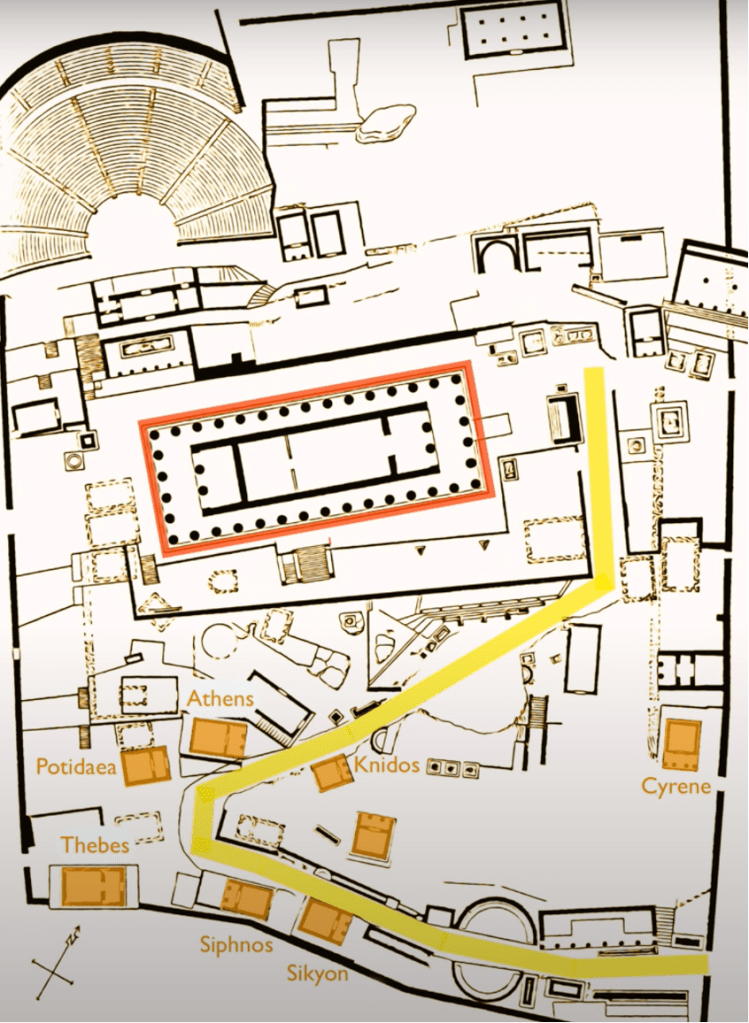

Although the site was a spot for all Greeks to come bearing gifts to offer and question to propose to the oracle, it was also a space where wealth, power, and influence was expressed. The offerings brought as devotional gifts to Delphi functioned as “token[s] of exchange,” used as leverage not only to assert wealth and status, but as cogs in a valuation system, with certain devotions gaining privileged access to certain gods.[11] This system of interaction occurring on the site between offerings, offerees, gods, and sacred spaces was reflected in the architectural plan of the sanctuary’s built environment, which was designed to mediate how people navigated the boundaries of space and the actions allowed within a space (Figure 11).

A sanctuary in Ancient Greece was a consecrated space. In these sanctuaries, the architectural program played a fundamental part in the purpose and meaning it held in the city, usually reflecting the needs of the community–allowing for variation and adjustment. The Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi was a prominent panhellenic site because it was not under the direct control of any one city state, making it both a neutral asylum, safe from polis conflict and a site for competition between cities for the attention and favor of Apollo (Figure 12). Poleis–or polis, were city-states or independently governed units in Greece, and represented one of the ways that Hellenistic Greeks formed group identities. Each polis was often ruled by kings or elected officials that had their own system of government, taxation, and currency. Eventually, control of the sanctuary site was handed over to the Delphic Amphictyony–a group of individuals from neighboring city-states that joined together to administer and keep the site apolitical. Delphi’s officials and priests actively worked to maintain good relations with various city-states. This diplomatic effort helped to prevent Delphi from becoming embroiled in political conflicts. Further, the neutrality of the sacred space was attributed to priestly authority, as these deific figures maintained their independence and impartiality. Delphi’s wealth, derived from offerings, donations, and treasures dedicated to Apollo, allowed it to maintain its independence. This financial autonomy enabled Delphi to resist external pressures and influences, remaining an intermediary site that transformed objects brought from near and far into totems of exchange.

Conclusion

Libations, votives, and sacrificial objects are central to Ancient Greek social systems, shaping the dynamics in which Ancient Greeks interacted with the world. These objects are immersed within a transitory process, representative of the channel of communication occurring between the Greeks and the Gods they worship. In this way, object offerings have agency through interaction and collaboration, actively participating through the symbiotic and reciprocal relationship occurring between these offerings and the Greeks, feeding prayers and favors to the gods. Object offerings oculate in this triangulation between object, the Greeks, and the gods, with this relationship influenced by two main factors: (a) materiality, which refers to the physical properties of the objects being offered. With some offerings granting more from the gods than others and each god positioned differently in a hierarchical structure, what the offers were as objects determined whether they were desirable to the Greeks and, by extension, to the gods; and (b) material agency, which suggests that the act of presenting the object as an offering grants it a value beyond material, one that reflects the religious, social, cultural, and ideological principles of Greek society.

[1] Rouse W. H. D. 1902. Greek Votive Offerings : An Essay in the History of Greek Religion. Cambridge: University Press, pp. 27.

[2] Brown, Bill. 2001. “Thing Theory.” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1: pp. 5.

[3] Peels, Saskia. 2016. “Thwarted Expectations of Divine Reciprocity.” Mnemosyne 69, no. 4: pp. 557.

[4] Hodder, Ian. 2014. “The Entanglements of Humans and Things: A Long-Term View.” New Literary History 45, no. 1: pp. 19–36.

[5] Mikalson, Jon D. 2009. Ancient Greek Religion, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. 2nd ed: pp. 389.

[6] Smith, A. C. 2011. Polis and Personification in Classical Athenian Art. BRIL, pp. 15.

[7] Osborne, Robin. 2004. “Hoards, Votives, Offerings: The Archaeology of the Dedicated Object.” World Archaeology 36, no. 1: pp. 7.

[8] Appadurai, A. (ed.). 1986. “The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 73.

[9] Ibid., 73.

[10] Neer, Richard T., 2001. “Framing the Gift: The Politics of the Siphnian Treasury Delphi.” Classical Antiquity. Volume 20, No. 2: pp. 296.

[11] Platt, Verity. 2018. “Clever Devices and Cognitive Artifacts: Votive Giving in the Ancient World”, in I. Weinryb (ed.), Agents of Faith: Votive Giving Across Cultures. New York: Bard Graduate Center Gallery Publications, pp. 2–19.