Introduction

The shift towards furthering advancements in scientific research and discovery that took shape during the Victorian period reflected a growing interest in answering biological and scientific questions surrounding the body, mind, environment, and the interconnection of each of these mysteries. Curious exploration into different ways in which we process information, understand sensory input and output and identify the positionality of the self in relation to the world became a central theme portrayed in visual culture, with notions of beauty in the natural world and aesthetic instinct becoming an intrinsic part of the Aestheticism Movement. The blending of the scientific and the artistic was nowhere as evident as in the paintings of Albert Joseph Moore, where the dichotomies between the motor and physical processes of the body, sensory expressions, and consciousness and unconscious are investigated, interpreted, and visualized within an artistic medium.

Dreamers and Apple

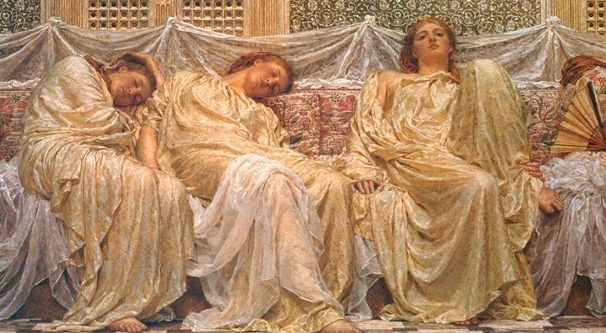

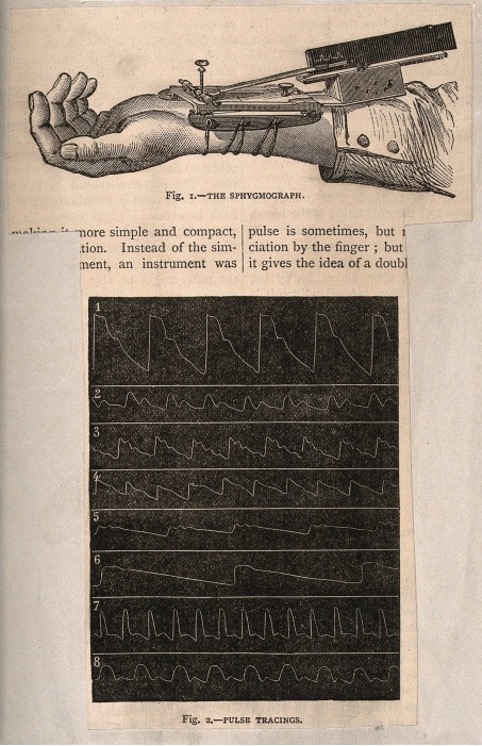

Representing various states of conscious and unconscious was a subject explored in the paintings of Albert Joseph Moore, where visual readings of rhythmic temporalities, relating to functions of the body and the mind, were contemplated and meditated on in discreetly subtle, symbolic, and decorative ways. Physical responses to stimuli were directly linked with different stages of consciousness and sentience, with these responses acting in response to sensory experience. This idea is linked to physiological psychology, the study of processes connected within the human body and the “unity of mental and neural events”[1]. Within this framework, sensory impressions were discussed in relation to the body’s visceral process, where internal and external input contributed to sentience, with the body described as never un-sentient, even when asleep. This visual representation of the relationship between inner and outer, or interior and exterior, is seen in Dreamers, where the active and ongoing action of motion is a quality used to show the interconnection of the self, body, and the external (figure 1). There is a fluid quality to the drapery behind the relaxed resting figures, creating an illusion of a steady stream and rhythm that evokes the continuous action of automatic and visceral processes–similar to blood circulation and bodily pulses. Additionally, pulsation seen in the repetition of the sloping and peaking drapery seem to be influenced by the illustrations created by the sphygmograph. The pulsometer (figure 2) measures and records pulse and blood pressure variations, and in effect creates these displays and tracings as shown through graphs. As an aid in the process of visual coding, this graphic method was an innovative system of recording and recoding the internal processes of the body into visual lines. These measurements were largely used to understand invisible processes within the body, capturing internal rhythms. The influence of these illustrative patterns seems to be utilized and integrated within Moore’s paintings, showing a connection between Aestheticism and scientific research.

The painting is a blend of traditional aspects seen in Aestheticism, showing beauty without realism, and crafting a scene that highlights ideas of harmony; however, it also emphasizes scientific references to pulsation and sensation, creating a shift in the traditions of Aestheticism that is explored further within Moore’s other paintings. The interplay of diagonals and horizontals gives a sense of the passage of time, elapsing from one moment to another, similar to notes within a musical composition–with sound being a form of external sensory considered in the exploration of beauty. This ties into the idea of cherishing fleeting moments, as well as the weaving and unweaving of ourselves that is found in the Aesthetic Movement and relates to the notion that sleep is “a condition of entire passivity”, [2] where the body is present and sentient, but not in active attention.

Additionally, the clashing patterns layered over and on top of each other play on the notion of movement between different states of altered consciousness, with the containment of the figures in this liminal gridded space giving the visual impression of moving from one state of being to the next. With the sort of automatic-ness and reverberation, the figures are indicative of the idea of “unconscious cerebration”, an instinctive and programmed response.[3] Further, the figures seem to represent different stages of consciousnesses and unconsciousness, with the two figures on the right seeming to be in various phases of sleep. The figure towards the middle however is awake and has a gaze held towards the viewer. This seems to convey the idea of cognizance and functionality of the mind even in these stages of unconsciousness that surround the figure. However, with these references to scientific thoughts and considerations in the painting, there are also references to the unknown. The pseudo figure created by carefully placed drapery and a fan on the right side of the composition seems to play into the enigmatic and mystery of the mind. Additionally, the positioned closeness of the figures is effective in challenging the distinctions made between conscious and unconscious, pointing out the lack of differentiation between the different stages of sleep and attentiveness.

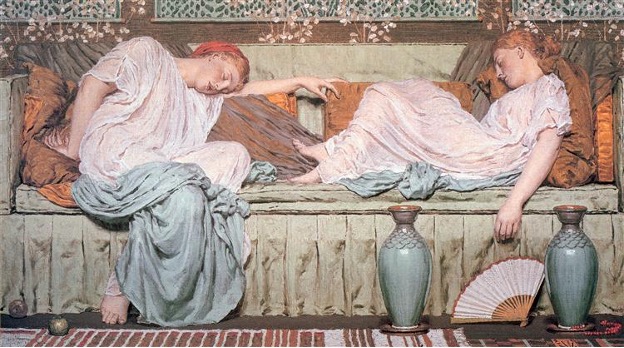

Moore further references the idea of transformation and shifting between metaphysical spaces in, Apple, showing two reclined figures in a state of deep sleep. A slow, steady tempo is carried throughout the painting in the drapery and body positions of the women–a sort of rhythmic unfolding of sleep. The pensive nature of the figures (figure 3) communicates the centrality of the human form and the human experience, an aspect of physiological psychology relaying the subjective physical experience. Additionally, the creased and wrinkled fabric seen throughout the space and in the garments worn mimic the curvature and folding movements of the body, a reflection of the fluidity found in bodily internal systems. The similar quiescent and stationary positions of the figures draw attention to their differences. The horizontal figure on the left side of the composition contrasts with the vertical figure on the right side of the composition. This seems to refer to states of being active and passive, or relating to the conscious and subconscious. However, there is also a sense of balance and harmony within the composition, with the fallen arm of the figure on the right bringing a verticality to the horizontalness and the horizontally outreached arm of the vertical figure to the left bringing a sense of stability and equilibrium to the overall composition. This idea of harmony is a visual tool used by Moore to show the mutual relationships that occur between us and our environment.

Red Berries and Lilies

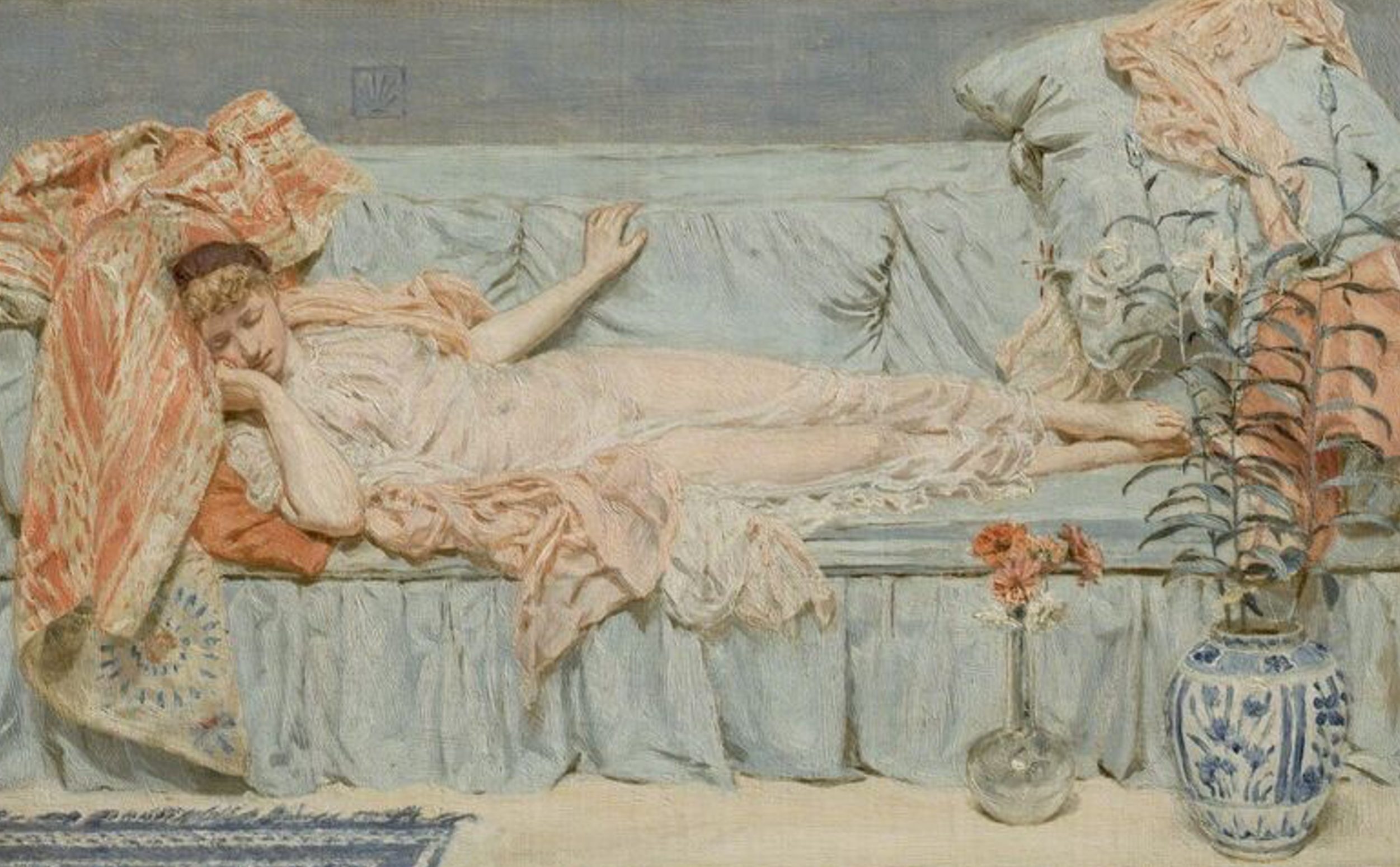

The contemplation of rhythm, balance, and a quantifiable relationship between science and beauty prompted a sense of action for the exploration of these concepts that seemed to have a mutual, reciprocal relationship. In Red Berries, Moore formulates a condensed space where stillness and motion are compact into one frame (figure 4). The pulsation and throbbing of the internal cardiovascular systems of the body are reparented in the swirling, waving, and curving seen in the wallpaper. Additionally, the pattern visually encapsulates the reading figure, forming around the body, seeming to actively interact with it as if a part of it. To this point, the act of reading a book seems to signify the mental disconnect of the figure from the surrounding environment and absorption into the activity of reading. The reference to anatomical forms and systems within the painting’s design and properties involves the consideration of the external and internal spheres as connected and “mutually constitutive”[4]. This represents the idea of unity, with visual impressions acting as a stimulus to bodily sensations. Additionally, the spatial and compositional intervals within the painting interact in a way that suggest a reciprocal relationship occurring around the body, where the experience of inhabiting a body is conveyed within a private, close space. Similarly, this closeness and intimacy with the human form is seen in Moore’s, Lilies, where there is a privateness in the showing of the body that contrasts the chaos and business of the external background surrounding it (figure 5).

Furthermore, the neoclassical representations of the female form, showing the classicization of the body, is evident in both Lilies and Red Berries, showing a reference to idealism that portrays women in a soft, supple form. This gentleness is also noticeable in the drapery that seems to fold around the figures. The tenderness in these representations of the body have sensual and sexualized undertones, where the female anatomy and reproductive organs are eroticized, in constant contact with themselves and with the environment around them. The reclining of the bodies reflects a state of being relaxed and comfortable, and the diaphanous, clinging fabric further emphasizes the sensual and intimate context of the paintings. The use of tapestry as an extension of the human flesh is a common theme within Moore’s paintings, with the fluid flow of the material representing the internal processes seen in the human body. This unbroken circuit and loop in the drapery forms a system of connectivity between the body and the self, where the rippling in the fabric and drapery over the bodies evoke the tracing of touch and pleasure– an emotional suggestion of sexuality associated with the female form. The influence of scientific research involving evolutionary developments and the functions of the body on ideas surrounding beauty and the perception of beauty is referenced in these works. The eye as a central receiver of external sensory became a focal point in the consideration of beauty and ideal forms of it, with the eye described as responding “strongly to stimulants such as markings, coloration, and secondary sexual characteristics”.[5] The attention to these elements within Moore’s paintings show a link between perceptions of beauty and the contemporary scientific findings of that time.

Birds and Blossoms

The disengaged figure is a reoccurring topic of consideration within Moore’s paintings, with various visual studies done within his works showing the transitory stages between sleep and consciousness that describe the conceptual and physical attributes of either stage of being. The awakened, engaged figure is a subject of study seen in Birds. The painting (figure 6) shows a woman stoically standing with a gaze positioned upward, this is a direct contrast to the paintings previously discussed where the figures are seen slump over or in relaxed reclined positions. Additionally, the erect positionality of the plant pointing upward seems to guide the woman’s gaze, reflecting the process and sequence of thought. This upward attention seems to convey the action of being awake, conscious, and attentive of your surroundings and external sensory. Additionally, the sharpness and alertness of the plant’s leaves and stems convey perceptiveness and sharp thinking. This relates to the consideration of how the mind responds to physiological processes.

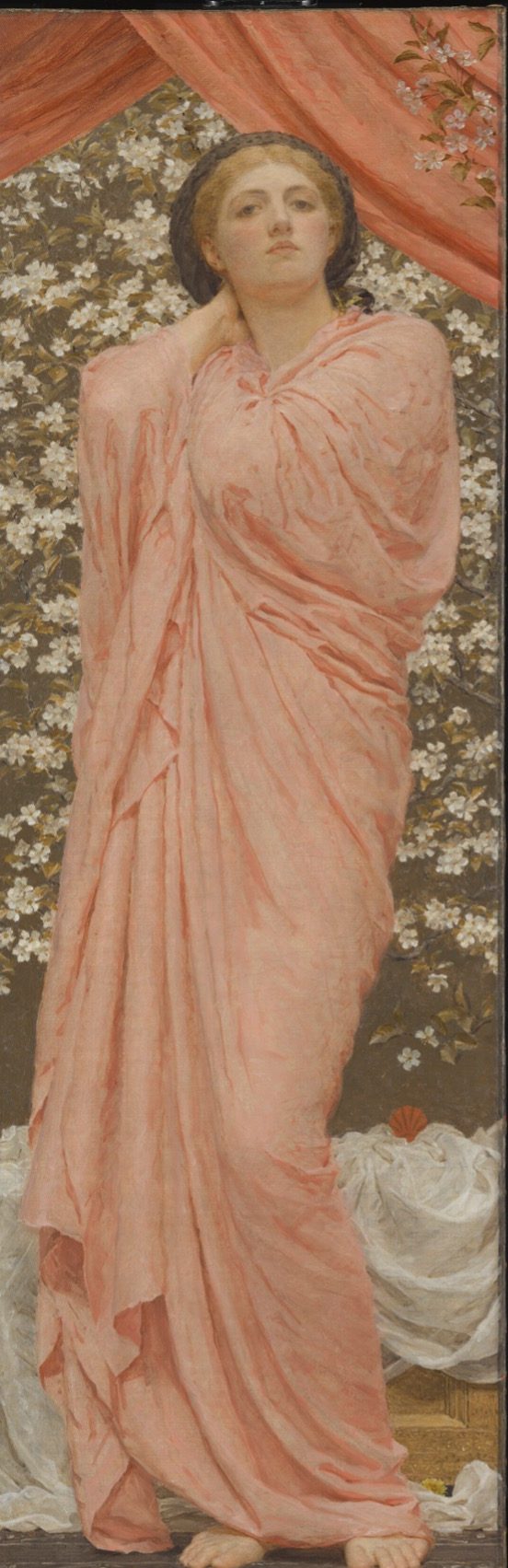

This notable attentiveness and awareness of surroundings is a quality also seen in Blossoms. The painting (figure 7) shows a posed women held in a gaze, a reference back to a more classical positioning of the body. The blushed cheeks, smooth skin, and softness of the features further push the narrative of reorientation to more classicized representations of beauty that align with ideal types. Similar to the figure seen in Birds, the body of the women is held in a spatially harmonious composition, dictated and framed by diagonals. The integration of nature and botanical forms within both paintings, seen in the textiles and next to the figures, point to idea of finding beauty within the environment and the influence of external sensory internally. Color harmony as a form of sensory was an influential concept with the emergence of Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory discussing the function of the eye, in terms of a “responsive eye” that is attracted to beauty. [6] This also relates to Darwin’s concept of sexual selection that further emphasized the value of beauty, regarding nature and the body. The use of color within Birds and Blossoms works as a filter–with Birds having a warm, yellowish hue that seems to compliment the colors seen within the gown tying in with the color of the bird and the hanging drapery. Additionally, the pink, rosy hue seen in Blossoms seems to compliment the coolness in the reds and whites seen in the fabric around the figure. The connecting of the different hues and tones in both paintings has a purpose of being aesthetically pleasing to the eye, a concept that is an integral aspect considered in Moore’s paintings . This further demonstrations the belief that the “sense of beauty [is] tied to pleasure given by form, color, and sound”, seeming to position the gaze and materializing within the paintings through the use of these elements to bring about a sense of harmony to the overall composition, evoking a beauty that engages the senses. [7] These contemplations of color reflect the idea of attracting the attention of the eye through the sensory of color and visual beauty, referring back to Darwinian conceptions surrounding the eye as a mediator of external stimuli. Pattern contributes to this concept as well, representing the beauty of botanic and natural forms into a systemized abstracted, flattened plane. Furthermore, the layering, stacking, and assembling of these patterns into these compact frames seem to communicate the various interactions that comprise of the sensory system, with interlaces of sensory experience and instinctive processes.

With Moore as a central figure in the transformation from Pre-Raphaelite styles to Aestheticism, this balance between nature and abstraction explored by Moore parallels the delicate balance of the ideal with the natural, or unity with diversity.[8] In many ways, the application of neoclassical forms of beauty alongside reformed ideas of the body and the mind is an intriguing quality in Moore’s paintings and instills a sense of humanness to the works, a mixing of the newly discovered with the unknown to form a balanced relationship.

Conclusion

There is a visual homogeneity to these introspective discussed paintings by Albert Joseph Moore that offer a foundation for the consideration of the interconnection between the human mind and body, as well as the various external systems that interact with it. The artistic blending of patterns, colors, and figures seen in the works of Albert Moore were motivated by the influence of scientific research and discovery on visual culture within the Aestheticism Movement. The absence in narrative present in many of Moore’s paintings were instead replaced by an aesthetic system that functioned to cultivate an orientation towards studying and understanding the principles of beauty, rhythm, and harmony rooted within scientific theories. Although contemporary scientific research and discovery about the systems of the body, our consciousness, and the sensate experience look very different from that introduced during the Victorian period, the basis of our understanding and examination of these concepts are credited to the exploration by Victorian scientists and creative thinkers like Albert Joseph Moore.

[1] Jacyna, L. S. “The Physiology of Mind, the Unity of Nature, and the Moral Order in Victorian Thought.” The British Journal for the History of Science. Pg.101.

[2] Cobbe, Frances Power, “Dreams, as Illustrations of Involuntary Cerebration”, Embodies Selves: An Anthology of Psychological Texts, 1830-1890. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1998.pg. 114

[3] Carpenter, William Benjamin. “The Power of the Will Over Mental Action”, Embodies Selves: An Anthology of Psychological Texts, 1830-1890. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1998. Pg. 99.

[4] Marshall, Nancy Rose, ed. 2021. Victorian Science and Imagery : Representation and Knowledge in Nineteenth Century Visual Culture. pg. 3.

[5] Larson, Barbara. “The Post-Darwinian Eye, Physiological Aesthetics, and The Early Years of Aestheticism”, 2021. Victorian Science and Imagery : Representation and Knowledge in Nineteenth Century Visual Culture. Pg. 194.

[6] Ibid, 191.

[7] Ibid, 195.

[8] Ibid, 219.